A conversation with Architectural Designer Kurt Hirschberg about the restoration of the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections and Exhibitions

April 1, 2024

I remember the first time I took a glimpse of the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse, which was coincidentally my first time visiting the South Street Seaport Historic District. I recall that I was fairly surprised to see a lighthouse-like structure in the middle of a busy crosswalk, between skyscrapers, traffic, and lower brick buildings, but in reading its informational plaque, its meaning quickly became more clear.

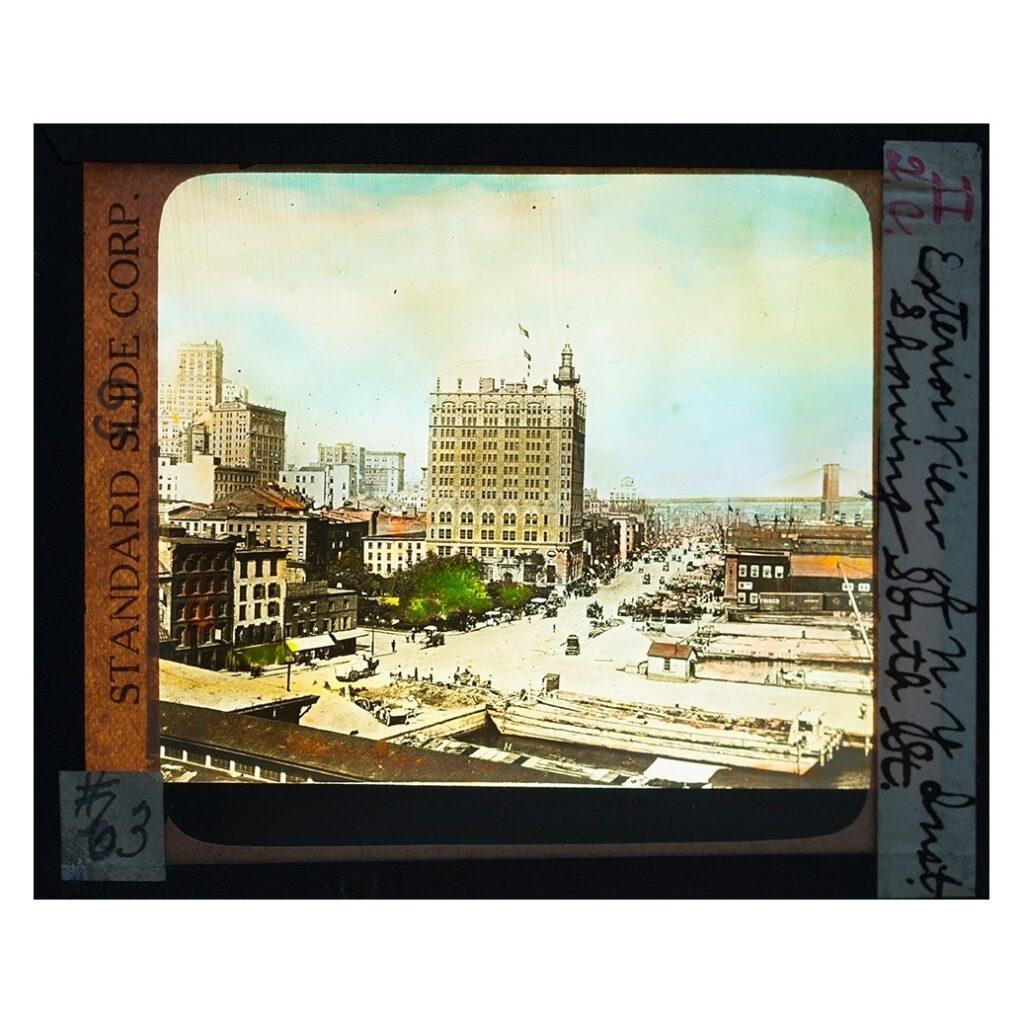

The structure is an accessioned artifact of the Seaport Museum, saved from demise in 1968 when the building atop which it stood was demolished. It was originally erected at the top of the Seaman’s Church Institute building, as a memorial to honor the passengers, officers, and crew who died as heroes when the steamship RMS Titanic sank after collision with an iceberg.

The memorial is a fantastic example of public art[1]Monuments, memorials, civic statues, and sculptures are the most established forms of public art, but what is a public art piece? According to Americans for the Arts, a nonprofit organization whose … Continue reading in the Seaport Museum’s collections. Public art pieces like ours are constantly vulnerable to the elements, obviously, and to the public, with their fingerprints, their gum and more. Regular maintenance for sculpture in the public domain is completely different than for sculpture in a museum.

Photo credit Richard Bowditch

Since I started to work at the Seaport Museum almost nine years ago, this artifact has been one of the most complicated to handle with regards to its stewardship, care, and accessibility. It’s only partially original, it has always required a comprehensive, expensive, architecture preservation plan, and it is a memorial dedicated to one of most famous tragedies in the contemporary times which shocked the world–and keeps fascinating people.

In 1912, Titanic and New York City were indeed the world’s greatest ship and the world’s greatest port. They were meant to come together, but the two would never meet. The sinking of Titanic sent shockwaves through New York society, intimately linking the superliner and the metropolis. But even if Titanic had avoided her fateful meeting with the iceberg on April 14, 1912, she would have only held the title as the world’s largest ship for a short time. The German steamship company Hamburg-America Line launched their significantly larger Imperator a mere month after the sinking of the Titanic. Nicknamed the “millionaire’s” ship by some, Titanic was crossing the Atlantic in April 1912 on her way to the city of millionaires, New York[2]If you are interested in learning more about the great ocean liners of 1900-1914 visit our exhibition “Millions: Migrants and Millionaires aboard the Great Liners, 1900-1914” in the Museum’s … Continue reading.

To learn more about the history of the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse check out this webpage. What I’d like to concentrate on in this blog is just some context tied to the construction of the lighthouse.

In the months ahead of the inauguration of the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse, the Seamen’s Church Institute included the following in an issue of their publication “The Lookout” in 1912:

This Lighthouse Tower is given as a memorial to every person without regard to rank, race, creed or color whose life went down when the giant vessel slipped beneath the waves. […] The Lighthouse Tower and TimebaIl will be the reminder New York needs. Sensational tales of harrowing accidents crowd each other for space in the newspapers and, very gradually but certainly, the average person, engrossed with his own affairs, becomes hardened and callous to stories of sudden death and its consequent bereavement to those who must live and mourn. This Lighthouse Tower Memorial must surely make all thoughtful persons realize afresh that the “Titanic” spirit must not die with the ship. It will make all careless people pause long enough to think-where they never thought before.[3]The Lookout, September 1912, Volume III, p.2

Last year, the Museum selected renowned preservation architects Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, Inc. from a highly competitive field to design a light-touch (and budget compatible) approach to the lighthouse’s restoration that prioritized first the stabilization of the artifact, followed by aesthetic improvements and restoration of the light and time ball.

I recently met with Kurt Hirschberg, Associate Partner from Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, to talk about his research and discoveries as part of the Museum’s ongoing efforts to restore the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse. Below is a transcript of our first conversation, as the project continues to develop.

Martina Caruso (MC): Maybe we should start off talking a bit about your upbringing in the field of historic preservation—and what influences you, beyond your academic background.

Kurt Hirschberg (KH): I have always had a strong draw towards historic objects. And a lot of people in the architectural end of preservation have a very strong object-driven basis. You’re drawn in saving objects that have little snippets of history. And on my end, I’ve had a strong draw towards historical objects with a mechanical nature, an interest I’ve had ever since I was young. I’ve always been drawn to what made them work and how they went together. It’s very much hand-in-hand with the historic preservation component because, in essence, you’re taking an object apart, figuring out how it was built, all the idiosyncrasies of it, and determining which idiosyncrasies are important to save and which aren’t. The lighthouse is an ideal example of an object that is also very much a mechanical artifact representing the finest engineering of its time.

MC: I’m sure many readers would be interested in learning more about how you approach restoring a memorial, a monument, or any historic site like the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse, compared to any other civic, government, or commercial building.

KH: Buildings exteriors, interiors, statues, monuments… They are all objects and the approach is the same. In the case of the Lighthouse, its beauty is the light. The lighthouse memorial is such a mechanical object, the whole process of how the time ball operated, the original Edison transformers that drove the original lanterns that still remain. It really is an amazing living object.

MC: So far, we spent a lot of time in the archives (the Museum’s and others) to research the lighthouse’s history and mechanisms. Is this always the case? What is the role of archives in your work?

KH: When you work with historic buildings, you know there’s always a story behind them. And I always like to go into a project knowing as much of that story. I want to understand what the evolution of the building was, what the changes were. So when you start to actually get into the structure, and take things apart, you begin to understand why decisions were made, why things changed. You begin to understand how materials failed over time, how they need alterations to accommodate failures.

Materials and records in the South Street Seaport Museum Archive.

MC: So digging into the archives also helps you understand how you don’t want to go back down that same path of making the same mistakes they did in the past. It’s really the same thought process we have in collections management.

KH: Yes, and it’s very enlightening just to have that understanding of what was driving the original design. The one thing that I’ve always found very wonderful about historic preservation work, is that whereas a lot of contemporary architecture is about the ego and the personality of the architect, historic preservation is the exact opposite. The architect’s role is to somewhat stand in the shadows and bolster the legacy of the original craftsman.

MC: When I talk to object conservators regarding the Museum artifacts in our collections, I am always struck by their chemical knowledge. Is it similar in the historic preservation field? Can you tell me a bit more with examples from this public art piece?

KH: Material science and the building’s stories are part of the evolution of the project. For example, looking at the steel structure in Titanic Memorial Lighthouse, we can see how things have failed and certain materials haven’t performed as well over time. We can see what drove a significant impact to deterioration on the steel framing on the inside, and on the sheet metal on the roof, and our hypotheses and assessments are confirmed by going through the archives, both at the Museum and at the Seamen’s Church Institute. We know that within a few years, they were putting goop on the roof because it was leaking right away. Understanding how systems failed ensures we don’t make the same mistakes going forward.

MC: We have to be able to preserve it, as much as possible, as close to what it used to be; but at the same time, preserve it in a way that is also more long term and the treatment is “reversible,” if needed to be.

KH: And this is really the big difference between object conservation and building conservation. Where in object conservation, you work in a very confined environment as you know, for example, what the humidity and the temperature range is going to be in your storage or galleries–and there, you can always go in with the lightest approach possible to restore the artifact. When you’re dealing with a building or an outdoor sculpture, there are many more constraints. The environment on the outside and the climate changes we are seeing in recent years and decades, vandalism, everything that that structure can be exposed to over time has to go into the material selection. So sometimes you do have to take a little more aggressive restoration approach for the long term preservation of the object.

MC: What has been the most exciting or surprising aspect of your research so far?

KH: Well, I think one of the most interesting things aside from the object’s legacy as being a memorial, it’s the fact it is a very interesting structure that has somewhat of a mixed up identity, almost right from the beginning. It might come as a shock to many, as over time, the structure was documented as a lighthouse, but going through the Coast Guard archives and doing the necessary research, we realized it was never actually registered as a functioning lighthouse. We realized early on while looking at the archives and the documentation related to when it was first opened, that the color of the light of the beacons, for example, was done in such a way, with that greenish hue, so it could not have potentially been mistaken as a lighthouse. So here you’ve got a hundred years of history of being a lighthouse when it really isn’t a lighthouse. It has always been a more decorative lantern luring sailors to the Seamen’s Church Institute.

MC: It always excites me when I am able to reframe the interpretation of an artwork, a name, or a history. It happens relatively often at the Seaport Museum (check out “Is It Thompson or Thomson?” blog entry, for example!). Was there any moment while you were looking into the archives and you had a “ah-ha moment”?

KH: I agree, that is exciting. That is the part that is the most exciting, but sadly I rarely have a “ah-ha moment.” Sometimes the piece isn’t there right away, even though you see it in front of you. It’s not until you start to look at 10 or 11 little snippets of pieces here and there that it all kind of comes together and you say, “Oh, okay.”

MC: And sometimes it is misinformation and word-of-mouth that moves new discoveries forward. Tell me another story.

KH: I have another perfect one for you. The one wonderful advantage to researching a building like this is it was constructed in the age of photography, and because of its prominence as a memorial, it was very well photographed right from the beginning. So when we started to look at the pieces of “Titanic Memorial Lighthouse Fresnel lens” in the Museum’s collections, labeled as part of the structure we started to have doubts. Thanks to the fact that there were dignitaries up on the maintenance platform at every anniversary of the Titanic tragedy who were photographed, today we can see what was inside the structure very clearly.

Titanic Memorial Lighthouse, 1913. Photographic print. Seamen’s Church Institute Archive.

The Titanic Memorial Lighthouse never had a functioning set of Fresnel lenses. We realized together that the fresnel lens in the archives could not have been for this lighthouse, but the rotating mechanism for the ball activation is original, and that one light fixture has the original transformers that drove the lights, connecting also to the original Western Union time clock that drove the time ball.

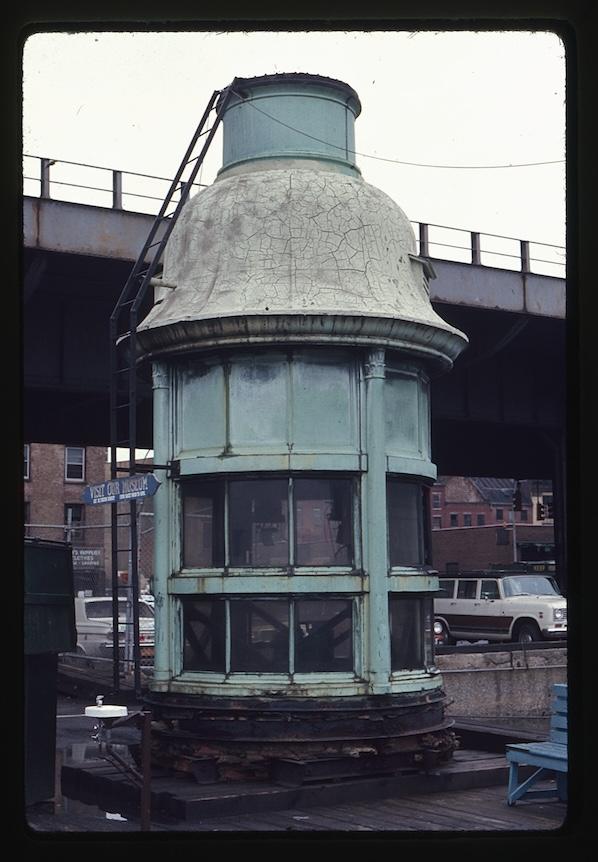

MC: All those pieces survived after the structure was moved to the Seaport, and it sat for seven years in an unprotected location on a pier, through one of the darker periods of New York City history for crime.

HK: Indeed, it is fascinating and actually quite amazing that we still have original parts of it. Then, when the time comes, it gets placed on top of a concrete base/podium, which was a little bit of an odd interpretation, but it was what the Museum was able to do in the early 1970s. Later, it served this purpose of being the ticket concession booth for the Seaport Museum, while also being a memorial.

Titanic Memorial Lighthouse, 1968-1976. 35mm slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archive.

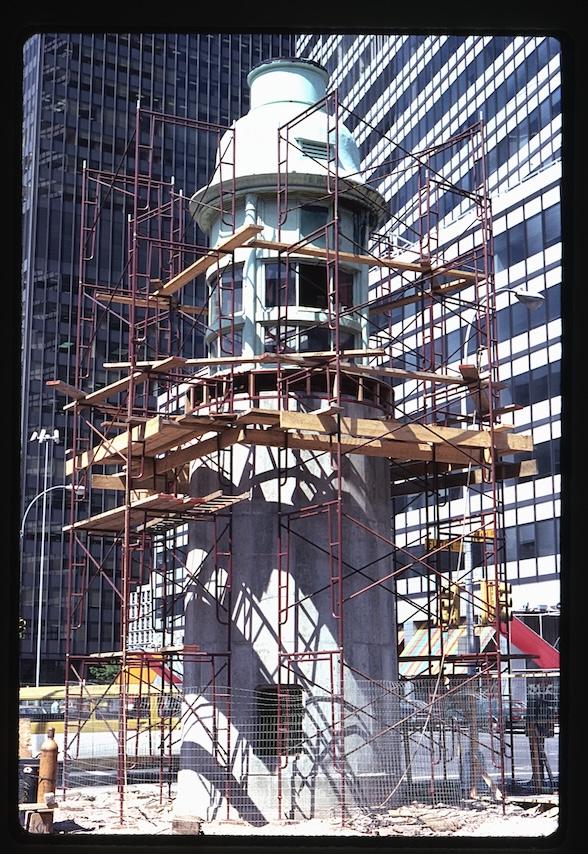

MC: The powerful component of this public art piece is the fact it is also one of the main entrances of the South Street Seaport Historic District. Since the top portion of the artwork is the historical memorial and the base is a later addition, are they being treated in the same manner in this restoration?

KH: We’re still treating all of it very much the same way. It will always be a memorial, but it also has always had been, by nature of what it replicated, a wayfinding aid. Whether it’s bringing the seamen into the Seamen’s Church Institute, or bringing maritime buffs into the South Street Seaport Museum. We are concentrating the funds we have to restore and elevate the original structure, which is technically only one third on top. The base will get lighter intervention, knowing that it’s not as historic. In some respects, the base is very much like a pedestal supporting the historic monument above.

MC: What is happening next?

KH: The process of design is also still pretty open, and we have various advisors and City-driven review processes. We’re currently out to bid requesting proposals from contractors on the job, including assembling prices and timelines, and we are hoping by early summer to actually be in construction. When we’ll start to mobilize on the site, we are going to be very mindful because it is such a prominent structure, and we will provide information for people so they can find out what’s happening.

MC: I look forward to showing and describing more the restoration work that we’ll be doing the actual memorial structure on future blog entries, including but not limited to its windows, the dropping ball mechanism, and the structure wrought iron gallery and gantry as the process unfolds. The South Street Seaport Museum particularly invites the descendants of Titanic passengers and crew to sign up here for updates on this project.

Additional readings and resources

Does Public Art Have an Afterlife? by Zachary Small, The New York Times, July 11, 2022.

Memorials and Monuments by Seth C. Bruggeman, as part of The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook, 2019.

Controversial Monuments and Memorials: A Guide for Community Leaders, by David B. Allison, 2018.

Commemoration: The American Association for State and Local History Guide by Seth C. Bruggeman, 2017.

Conservation of Public Art, The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, Fall 2012.

Whose Monument Where? Public Art in a Many-Cultured Society, by Judith Baca, from Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, edited by Suzanne Lacy, 1996.

The Titanic Memorial Lighthouse by Michaell J. Mooney, published in The Lookout, December 1984.

Walking Around South Street by Ellen Fletcher Rosebrock, 1974.

References

| ↑1 | Monuments, memorials, civic statues, and sculptures are the most established forms of public art, but what is a public art piece? According to Americans for the Arts, a nonprofit organization whose primary focus is advancing the arts in the United States, the term public art refers to art that is in the public realm, regardless of whether it is situated on public or private property or whether it has been purchased with public or private money. Usually, but not always, public art is commissioned specifically for the site in which it is situated. Public art can also be a form of civic protest or take the form of a transitory art, such as performance, dance, theater, poetry, graffiti, posters, and installations. For a more in-depth understanding of the term public art visit the Americans for the Arts website’s Public Art page. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | If you are interested in learning more about the great ocean liners of 1900-1914 visit our exhibition “Millions: Migrants and Millionaires aboard the Great Liners, 1900-1914” in the Museum’s introduction galleries at 12 Fulton Street. We have also hosted various public programs on the topic, including the past program still available to watch on-demand on our website titled “Beyond Titanic: Travel and Immigration in the Era of Ocean Liners” in which the Seaport Museum held a conversation with special guests author, travel writer, and lecturer Theodore W. Scull and historian and educator William Roka about the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by immigrants and millionaires prior to, during, and after the “Era of Titanic.” |

| ↑3 | The Lookout, September 1912, Volume III, p.2 |